Time won’t erase the memory

Of her bye and bye,

We’ll have to face life hoping

Somehow we’ll know why.

--“Song for Lise,” Marc Gawthrop

[July 29th marks the fortieth anniversary of the death of my younger sister, Lise Ann Gawthrop, at age nineteen. Until now, the only thing I had ever published about Lise was a religious testimonial that appeared in a national Roman Catholic scholastic publication some weeks after her death. I haven’t read that piece in decades. If I did now, I would not recognize the person who wrote it. What follows is my current understanding of what was and what might have been. I hope you like it.]

July 31, 1984

Papineauville, Québec

The first of two long-distance phone calls from British Columbia came at around noon on a sweltering mid-summer Tuesday in rural Québec. My mother, her voice trembling, told me that my younger sister Lise had gone missing on Sunday. She was supposed to have reported for work that night at a summer camp on Thetis Island but never showed up. Last seen at the Nanaimo River, she must have stopped there on her way to the Chemainus ferry. Her bicycle had been found against a tree near a trail to the river. As we spoke, Mom told me that Dad and three of my brothers had gone to the river to join the search effort. She had called my second eldest brother Marc, then living in Mexico City, to tell him. Suzanne, my older sister, was at home with her.

The moment I heard the word “bicycle” I knew Lise was dead. She was not someone who shirked responsibility; the bicycle was proof that she never left the scene. The Nanaimo River had taken so many lives already, so now hers must have been another. I could feel it in my bones; I could hear it in the dread, the fear, in my mother’s voice, an unsettling fragility I had never heard from her. At that moment, the agony setting in, I wanted nothing more than to be back in Nanaimo with her and the rest of the family—not in Québec, where I was serving as a volunteer participant in a national youth program.

For the next five and a half hours I wandered around in a fog of anticipatory grief. I did my best to concentrate on the day’s project—the construction of a wooden gazebo for an upcoming festival—but everyone could see my anguish, so I was excused early. Heading to the local Catholic church on foot, I went inside and knelt down to pray, unconvincingly, for my sister’s life. The parish curé listened compassionately to my stories about Lise. Later, back at the project house when our workday was done, my program mates did their best to provide distractions, a few inviting me out to the lawn for a casual game of touch football. But when the front door opened and another shouted, “Long distance call, Dan!”, the few seconds it took to get back to the house were the longest of my life.

“I’m afraid I have some bad news.” It was my father this time, with the same words he so often used as a doctor addressing patients or their families—only this time it was to his youngest son. His voice was weak, his spirit broken.

Divers had found Lise’s body.

Despite being born eighteen months apart and growing up together as the last two of seven children, my younger sister and I never really knew each other. In early childhood, Lise and I competed for the attention and favours of our parents, four older brothers and older sister—a competition I could not win, Lise being the youngest and most precious child. Later, it was a clash of egos caused by the usual adolescent insecurities as we fumbled our way towards adulthood. We also had different ways of seeing and interacting with the world. Lise was the practical problem solver and I the dreamer, she the science & math whiz and I the liberal arts intellectual/aesthete; she was bold and direct in her speech, I more likely to hold my counsel. Although we usually got along fine among the family, we seldom hung out in public and had different circles of friends—hers much larger. Every now and then, one of us would feel hurt or betrayed by the other’s insensitivity. By our mid-to-late teens, for reasons neither of us could articulate, our guards were up with each other.

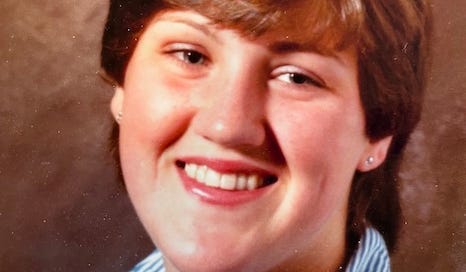

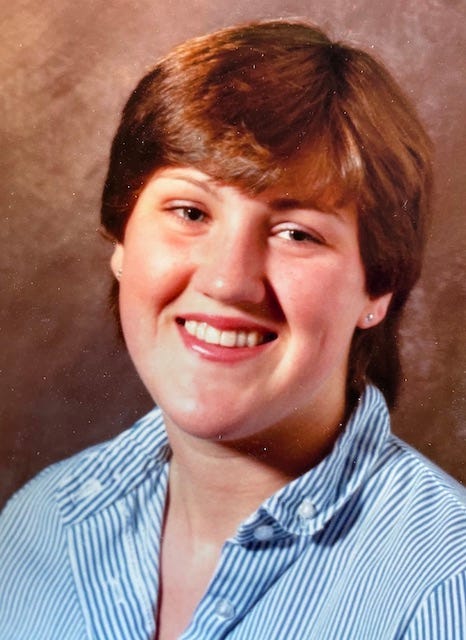

I was frustrated by the rift between us, for I not only loved my sister but admired her. What was not to like about Lise’s lust for life, her daredevil spirit, her apparent mastery of everything she attempted? Lise was a physical presence: a big-boned gal, athletic, as dominant on the grass hockey field as on the ski hills of Green Mountain, Forbidden Plateau, or Mount Washington, her big smile and laugh lighting up everyone around her. She had abundant self-confidence. Although we both learned to swim in our backyard pool, she had the drive and discipline to complete the skill levels required to become a lifeguard, like our brother Rob; I did not. Though we both learned to ski at the same time, she soon eclipsed me on the slopes with the power of her downhill technique. In school, she skipped a grade; I did not. Perhaps I was jealous of the comparative ease with which everything seemed to come to her.

At one point, substance use became a matter of contention. Lise was into marijuana and loved getting baked on the mountain, at the beach, or at home by the pool. When our parents were away she sometimes hosted a party, the next day opening every window to rid the house of its pot smoke residue. Once, when she was seventeen and I just shy of nineteen, I confronted her with my concern: she was becoming a stoner, I said; the weed could have harmful effects on her life. This was pretty rich, coming from someone who had started drinking at fifteen and was well on his way to juicerdom three years later. Lise pointed out my hypocrisy in no uncertain terms, and I would soon pay for it. Not long after that conversation, I hosted a party of my own—or, at least, tried to. Before the party had even begun, I decided it would be a good idea to wash down a grilled steak dinner with three-quarters of a twenty-sixer of Canadian Club rye whiskey. By the time my guests began arriving I was falling down drunk, incapacitated, and had to be removed from the scene. Lise, declaring the party over, dragged me to the upstairs bathroom and guided me into the tub, turning me on my side as I lay down so that I wouldn’t pull a Jimi Hendrix and choke on my vomit after passing out. The next day, she told me how she and Rob, who also attended, had taken care of me. It might be overstating things to say that Lise saved my life, but not to say that she may have prevented my death. I felt like I owed her one.

In February 1984, Lise was in her first year of Biology at the University of British Columbia while I was doing a double major in English Lit and Political Science at the University of Victoria. We hadn’t been in touch since the Christmas holidays when I received a greeting card from her, its cover bearing the painted image of a black-and-white cat that resembled our beloved pet Mojo. Inside the card, both pages and the back were filled with Lise’s neat, loopy handwriting. After a chatty update on her semester at UBC, she got to the point:

Where do I begin? First of all Dan, our lack of communication is staggering! Whatever the reasons, you really don’t know me or what I am feeling or how I reacted to situations. You’ve been assuming, making judgements (or decisions) about me, and because I’ve never given you any reason to believe otherwise, you’ve never thought otherwise. It’s my fault. I’ve not been communicating, and not because I don’t want you to know me but probably because I never thought you were interested. Well, maybe not ‘not interested,’ but I’ve always felt you didn’t want to hear about it because…you were tired of listening to me…

Please don’t feel that I don’t want to talk to you, that I’ve got better things to do, etc. That is so wrong! I love you! And I enjoy your company, only when we get together, it seems that old idiosyncrysies(sp?) get in the way, and we fall back into the pattern of playing our little games. It’s shit, I know, but we just haven’t had the chance. I’ve grown up a lot since I’ve been here, and all the things that are happening to me are showing me more and more about people and life. And that in turn helps me to grow in myself and in relationships with others…

I find it hard to TRULY express myself in writing, unlike you Dan. I need to hear specific questions to understand what you want to know. We’ll have the chance soon, I hope…And please feel good about what we have already shared—it’s more than a lot of other brothers and sisters…

This was an extraordinary olive branch—and well expressed. I don’t recall my response, but Lise’s letter began a correspondence that signalled a positive change in our relationship. We were both eager to see each other, but circumstance intervened to prevent us from meeting: when the academic year ended, we missed each other back home in Nanaimo by a few days. Lise returned for just long enough to pack her bags and head to the small northern B.C. village of Horsefly, joining our brother Philipp for a tree planting gig. I was off to Québec, having decided to take a year off studies to participate in Katimavik, a national youth program Philipp had done seven years earlier. The first of three placements lasting three months each was in the small town of Papineauville, located on the autoroute between Montreal and Ottawa.

On July 26, I received another handwritten letter from Lise, this one six pages long, at the Katimavik house. The letter, dated July 14 and then July 19, was written on three sheets of stationery bearing a colourful pastoral scene with “Jesus is the Shepherd of Love” as the header, and words from John 10:11 as the footer: “I am the good Shepherd. The good Shepherd giveth His life for the sheep.” Lise described her tree planting experience with Philipp as both a trial and a revelation, the latter more powerfully so because of her love of the great outdoors. Then, courtesy of Elton John and Bernie Taupin, she offered this:

One day, out on the block while I was planting, I was talking with the Lord (as I often did because insanity lurked behind every rock and was parasitic to every bug—thousands of them!), and all of a sudden I started singing:

Daniel my brother, you are older than me

Do you still feel the pain of the scars that won’t heal?

Your eyes have died, but you see more than I

Daniel you’re a star in the face of the sky…

I couldn’t believe how much I missed you! What a silly childhood relationship we had! I now pray for the opportunity for mature growth in Jesus’ name – that we may throw away all the old pains and try to heal the scars with the love we know comes from Jesus. In his glorious name! And through him I can see all I’ve done to hurt you—and me. Let us grow, in faith and love, together, my brother.

She went on to describe life at Camp Columbia, the Anglican summer camp we both attended as kids but which she had embraced more fully than I had. (I attended once as a camper; she attended for several summers, later serving as a counsellor and then lifeguard.) Having finished the tree planting gig and returned to the coast, she had already put in a couple of week-long sessions at the camp and was looking forward to going back for more. Thankfully, there was just enough of the naughty old humour in this letter to reassure me that Lise hadn’t gone completely soft. Describing the challenges of working at a co-ed camp where the girls were aged nine to sixteen, she lamented the “disco bitches” herd mentality of an age group from which she was only three years removed: You know the type—crème blue eye shadow, curling irons and Michael Jackson/Culture Club groupies. Help! Give me patience, Lord. I’ll need all the help I can get!

Then, reminding me to write to her, she told me she loved me and signed off. The day after that letter arrived, I travelled to Ottawa for the long weekend. I did not begin composing a reply until I was back in Papineauville on July 30. I had just begun telling Lise what a wonderful person I thought she was becoming when, the next day, came those two long distance calls...

Forty years later, the most remarkable aspect of Lise’s letters and my own private journals in the weeks following her death is the deep well of Christian faith running through both. Given my abandonment of God and religion a few years later, and the passage of decades since then, it is hard to go back in time to unscramble the mind of an earnest, virginal twenty-year-old responding to the most traumatic event of his young life; harder still to see through the haze of Lise’s and my respective “spiritual journeys” and get to the heart of what had prevented us from communicating. But here’s my best take on what went on and what might have been…

Born again, Lise had recently converted to a Protestant faith rather than the “one true and apostolic Church” in which we had been raised. I was born again too, but within a liberal form of Catholicism—one that emphasized Bishop Remi De Roo’s “People of God” concept of community rather than the doctrine-oriented, right-wing faith of pre-Vatican II Rome. But we were both closeted about something. For Lise, it was her new-found faith itself, a deeply personal part of her life that she told me was difficult to share. (Perhaps it seemed at odds with her purple haze fandom of Led Zeppelin, a band often mistaken for Satanists thanks to Jimmy Page’s dilettantish fascination with the occultism of Aleister Crowley.) For me, it was that I was using “spirituality” as a way of both hiding the truth about who I really was and putting off any decisive action toward authenticity, fearing its consequences. But Lise was willing to share her secret with me; I was getting close, but was not quite ready to share mine with her.

In the wake of her death, our family and Lise’s friends all reflected on what we had lost. Mostly the obvious things. A life snuffed out at nineteen, never to reach its full potential. The loss of the youngest child for the parents (her final conversation with Dad on July 29th had been to wish him a happy birthday), the youngest sibling for her sister and brothers, and a great friend for so many. A community deprived of the gifts she had to offer, with all those what-ifs about her future. Many of us thought Lise would have become a marine biologist, combining her love of water and passion for animals with her thirst for knowledge. Others thought she would follow in our father’s footsteps and pursue a medical career. There wasn’t a boyfriend as far as we knew, but most of us assumed that she would one day marry and have kids.

Part of my grief around Lise’s death involved a fresh regret: we had been deprived of the opportunity to test our new-found mutual respect. There was nothing in those letters to suggest that her Jesus-centric faith came with the baggage of fundamentalist morality. On the contrary, Lise seemed to be all about the gospels of love. Had she lived, I am certain, she would have wasted no time getting to the bottom of my awkward, unconvincing faith. For one thing about her that never changed was her low tolerance for bullshit; she would have called me on mine, once she could see that I was using faith as a form of avoidance. After that summer, I would have come clean with her because she had gained my trust. Had she lived and I told her during the Fall of 1984, Lise would have accepted my being gay. She wanted those she loved to be true to themselves; she disliked the artifice, the fakery, of emotional hiding.

My disclosure, too, would also have come as some relief, for it would have explained certain things that had happened between us. Like my hard drinking, for example. Or that tension-filled beach vacation in Mexico, where Mom and Dad took us for Christmas in 1979 when I was sixteen and Lise fourteen. During the trip to Mazatlán, I’d made a point of cramping her style: not leaving her alone, being sarcastic, always contradicting her. It got so bad that even the other adult couple traveling with us called me out for my childish behaviour, telling me to smarten up. If Lise were alive today, she would have a good laugh retelling the story of what was really going on: that, unbeknownst to her and everyone else in our group at the time, I was competing with her for the attention of the same cute guy, a California surfer about a year older than me whose family was staying at the same resort. A dark-haired white boy with a nice tan and sexy red swimming trunks. My behaviour had been passive aggression: Lise was in the way. (Yes, even from the closet, I could be a real bitch.)

No disrespect to my surviving siblings, who were supportive once I was ready. But with Lise as my confidante I would have come out of the closet five years before I actually did, thus becoming an adult that much sooner. This would have saved me the anguish of dealing with the consequences of embracing my sexuality (losing friends, alienating another by bailing on my duties for his wedding, chickening out of a TV news job offer) at the very moment I was beginning my career in the traditionally macho field of journalism. On the other hand: had I begun a sex life as early as 1984, it’s possible that AIDS and its far worse consequences would have caught up with me. We’ll never know, just as we’ll never know how much better a person I might have become with Lise in my life all this time, our competition resuming in a healthier way as we pushed each other to succeed, celebrated each other’s triumphs, and consoled each other in failure. Instead, she died. And I retreated into an emotional shell.

After Lise’s death, my family learned just how deeply she had affected the lives of others. Among the four-hundred and fifty mourners who attended her celebration of life at St. Peter’s parish was a large contingent of counsellors from Camp Columbia. Their choral rendition of Lise’s favourite camp song, “Lord, let me be like you,” had everyone in tears; at the reception and then at the camp, where we spread her ashes a few days later, the stories they shared revealed a side of Lise we had never known: devout and committed, a leader in faith among trusted friends. Decades later, in 2013, Marc posted a photo of Lise on a Facebook page dedicated to Nanaimo stories, encouraging friends to share memories of her. In response, dozens of people did. There were tales from high school, of making a mess of the Gawthrop kitchen while baking cupcakes, of pinecone fights with boys up the street after Lise led a raid of their treehouse, of visiting the cemetery outside St. Peter’s parish to tidy up a friend’s gravesite, of a woodworking class in which Lise made a hash pipe that was later confiscated, and more. Many of these people, some of whom we never knew, recalled Lise with the same words: “a beautiful soul.” This was one example of how Facebook can do some real good: the response to Marc’s post had brought Lise back to life, if only virtually, through stories. My siblings and I, and our father, were deeply moved.

We will never know exactly what happened to Lise when she met her end on July 29, 1984, but one theory has never sat well with me: the notion that she drowned while swimming alone, breaking the cardinal rule for every lifeguard. This was the unfortunate news angle that a Vancouver Sun reporter chose for a story about my sister’s death, and some still believe it. Had this reporter taken the time to visit the river, and the exact spot where Lise was found—as I did, the day after I arrived from Québec—she might not have felt so at liberty to go with that angle. If Lise had done any swimming that day (and a few people who spoke to us afterward swore that she had, saying they had seen her in the water where others swam), it would have been some distance down river from where she was found. Her final resting place was in the pocket of a large rock that the water’s heavy flow had pulled her into and jammed her against. How strong was that water’s flow? So strong that the divers who found Lise’s body had to tie a rope around her wrist to pull it out. Nothing bigger than a river fish ending up in that pocket could have escaped it. During that summer, this section of the river had a deep, slow-moving current with a powerful undertow that led straight into rapids. For several metres upstream from the rock, there was no obvious entry point for a dip. Any swimmer, never mind a lifeguard of Lise’s experience, would see right away that this was not a place for swimming.

When I visited the spot four days after her death, however, I imagined that Lise would have found it a great place to catch some rays and soak her feet. (Whether it was a Mexican beach, a friend’s sundeck, or the pool patio at home, my younger sister was into “serious tanning,” something she even noted in her last letter to me.) About thirty feet upriver from where she was found—and just a few feet away from where she left her belongings—was a long, flat piece of rock on the water’s edge that was perfect for sunbathing. I could easily imagine Lise lying down on that very spot, her feet cooling off in the water, and then—deciding it was time to return to her bike and continue on her way to Chemainus—getting up to leave. And this is where I could see what might have happened, a combination of factors and split-second decisions that can prove the difference between routine and tragedy.

Despite being a dedicated sun worshipper, Lise was not immune to the effects of extreme heat. At least once that summer, while tree planting in Horsefly, she had briefly fainted. This might have been on her mind when she decided to stop at the river: after riding her bike from Departure Bay, she needed a break from that punishing stretch of asphalt along the Island Highway, fully exposed on a clear afternoon in late July. Once she had cooled off with a swim, she must have taken the trail upriver to enjoy a bit of solitude before continuing on her way. I can imagine the moment she decided to leave after several minutes baking in the sun on that rock: standing up too quickly and getting dizzy, perhaps fainting, then falling into the water and being dragged away. Or, rather than pulling her feet out of the river to rise from the safety of dry rock, standing up in the water and then slipping on smooth rock with nothing to grab onto as she was pulled in. One of those two scenarios, I believe, is what killed her: a freak accident. One moment a vibrant nineteen-year-old, with a bright future ahead of her. The next? Gone forever.

For many years afterward, every now and then, I would have the same recurring dream about my younger sister. I would be out in public somewhere when Lise would appear from out of the blue, as if she had never died but instead was ghosting me because she preferred to be elsewhere. I would confront her, asking why she had abandoned me, but she would never give a straight answer before disappearing again. Then in 2019, my husband Lune and I visited Bali. On our first day, we decided to explore the rice farm where we were staying. A few minutes into our trek, we had just finished walking down a steep trail into a ravine our hosts had told us led to a waterfall (we didn’t realize we had taken the wrong trail) when we came upon a short bamboo bridge. About six feet long, it was surrounded by bushes, giving no clue of what lay beneath it. Lune crossed it first, I followed. When I stepped on it, the whole thing collapsed. Down I went, plummeting into darkness for what seemed a few seconds, the free fall long enough to be terrifying and for my life to flash before my eyes.

Before I could hold my breath I plunged into a pool of moving water, triggering a disoriented panic. As I began thrashing my way upright and to the surface, I suddenly had a sharp vision of Lise in her final moments, desperately trying to escape the pocket of that rock in the Nanaimo River. Once I could stand firmly on my feet and breathe again, the rushing water up to my chest, I looked up to see that Lune had cleared away the rest of the damaged bridge to let the light in, revealing my passage: I had fallen more than twenty feet into a crevasse, my head somehow missing several outcroppings of rock on the way down. Pondering the vision of Lise that had come to me while I was still under water—of the possibility she might not have been knocked out by that rock but was still conscious and struggling to get out, of the difference in our fortunes and of how close I had just come to sharing hers—I burst into tears.

Since that brush with death in a Bali crevasse, the dreams about Lise have not come back.

Perhaps, after all this time, I am finally letting her go.

Marc Gawthrop composed “Song for Lise” after learning of her death while in Mexico City. Days later, in Nanaimo, he performed it at her celebration of life. It slayed me at the time—how did he manage to hit all those high notes without his voice breaking?—and it still does on the rare occasion that he plays it. Many years after Lise’s death, he recorded the song at S&S Studio in Saanich. Syl Thompson played guitar and bass.

You can listen to it here:

Beautiful, Dan. Very moving. What a gift to be offered this vulnerable window into your and Lise's relationship. Thank you. It has stirred much in me and I'm sure we'll talk soon. Maybe by then I'll have more words to wrap around what is surfacing.

I now feel like I know my auntie better. Thank you! Love you.